by Maryam Zaringhalam

In 2002, a group of NASA-funded bioengineers at New York’s Touro College succeeded in producing the world’s first cell-cultured meat—a filet of fish. They celebrated this extraordinary creation as any other human would: “an associate briefly marinated the explants in olive oil, chopped garlic, lemon and pepper, covered them in breadcrumbs, and deep-fried them.”

“It looked and smelled pretty much the same as any fish you could buy at the supermarket,” project leader Morris Benjaminson, a veteran of NASA waste disposal projects, recounted later. Sadly, FDA regulations prohibited his team from eating the fish they had grown and seasoned. Then again, they may not have wanted to. While their creation was referred to as filet, it was technically the outgrowth of “muscle chunks cut out of a large goldfish…washed in alcohol, and immersed in a vat of fetal bovine serum, nutrient-rich liquid extracted from the blood of unborn calves.”

Sensing that there were more convenient ways to feed their astronauts, NASA opted not to continue funding Benjaminson’s research. His experiment proved influential elsewhere, in the development of the nascent cultured meat movement — inspiring the 2004 founding of New Harvest. Since then, the cultured meat industry has exploded. As of 2018, nearly thirty companies around the world are now racing to be the first to get their product into a grocery store or restaurant near you.

The drive for more cultured seafood, however, hasn’t come quite as far since Benjaminson’s goldfish filet. Although, as New Harvest’s 2019 review of cell-based seafood notes, the physiological properties of fish cells make them uniquely well-suited to cell culture, so far only six companies are currently working on ways of growing fish in the lab. Their procedures have evolved since Benjaminson’s experiment, but they overwhelmingly still rely on the same fetal bovine serum for their growth. This represents a crucial hurdle, as many of these companies are committed to only going to market with an entirely serum-free media. Much rests on their eventual success: the vibrancy of coastal economies burdened by overfishing—not to mention the lives of countless fish—as well as the environmental toll of current modes of seafood production. Luckily, researchers are looking for ways to innovate around this problem.

TOWARDS A TRULY ANIMAL-FREE FISH

Notable among them is one Cameron Semper. A postdoctoral fellow at the University of Calgary in Canada, Semper has tasked himself with engineering a new kind of artificial environment that can nurture the growth of fish cells. Last fall, he began his fellowship with New Harvest. His goal is to find the right recipe for a fish-specific growth medium that contains all the ingredients needed to culture an edible fish filet. This requires identifying fish-specific factors and synthesizing them in the lab. He aims to concoct a “serum-free” medium that can be made without animal byproducts.

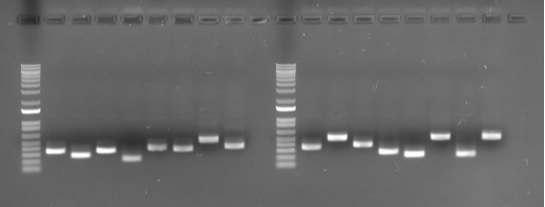

DNA gel of synthetic genes coding for fish growth factors

While companies have been experimenting with serum-free formulations for cell-based terrestrial meats, they have yet to develop a formula that is cost-effective for large-scale production. Furthermore, these media have yet to be fully optimized for fish. Last month, foodtech startup BlueNalu unveiled the first slaughter-free slice of yellowtail, but the fish cells were cultured in a serum-free solution containing plant proteins, rather than those specific to fish. With New Harvest’s support, Semper has made headway identifying the core set of fish proteins necessary for a healthy cell culture. He hopes such an innovation will crack open the field of cultured seafood. Now, he’s excited to put his preliminary work to the test. “This is a proof of concept experiment, initially,” he explains. “We want to know: Are these growth factors going to perform at least as well—or hopefully better than—the bovine growth factors when culturing fish cells?”

HOW TO MAKE AN IMPACT

This has been a long time coming for Semper, who grew up in Canada when the country’s massive fishing industry was in crisis. He was in elementary school during the 1992 collapse of the Northern cod fishery along the Atlantic coast. The fishable biomass fell nearly 99 percent at the time—from nearly three million tons in the 1960s to tens of thousands in 1992—due to decades of overfishing. On July 2, 1992, the Canadian government placed a moratorium on cod fishing, and this wreaked havoc on the local economy, leaving nearly thirty-thousand Canadians without a job.

Warming waters and shifting flow patterns altered by climate change are exacerbating the effects of overfishing in Semper’s native Canada. Environmental advocates are sounding the alarm in British Columbia, a province famed for its salmon, which has seen drastic declines in its seasonal spawn. That decline has rippled through the ecosystem and impacted other animals, like local bears, who depend on healthy salmon stocks. “I’ve always been aware of this trophic cascade that can result from overfishing and over exploitation of fisheries,” Semper says.

But his path to cellular agriculture wasn’t all that direct. Something far more adorable led him to the field: Esther the Wonder Pig. The 650-pound pig became an Internet sensation in 2013 thanks to her playful antics and famously funky wardrobe, and has become a symbol for cruelty-free and compassionate living. Semper recalls the impression Esther made on him. “She had quite the personality. I never ate a lot of pork, but she had too much personality to be food.” He began cutting down his meat consumption, but still missed hamburgers. Cellular agriculture offered him a solution to his moral conundrum, one that also satisfied his love of science. “Basically,” he says, “I wanted to eat hamburgers without feeling too guilty!”

Around the same time, Semper read about the first hamburger grown from cells. He was excited by the idea, though less excited by its $280,000 price tag. After completing his doctoral degree, he saw an opportunity to apply his expertise as a protein biochemist to advance the field. His graduate research focused on the relationship between protein and RNA, but this work felt removed from having an immediate impact. “I didn’t have illusions that I was changing the world with my PhD,” he says, “but I knew there was a chance to feel that in research.”

THE NEXT STEP FORWARD

For his postdoctoral fellowship, he joined the lab of Alexei Savchenko, who had recently received funding to advance the development of meat alternatives. Reading up on the field, Semper noticed that fish were largely overlooked. In the few studies that did focus on fish, he was struck by the continued reliance on animal products like fetal bovine serum. “When I saw that, I thought, ‘Why are they using cow serum to grow fish cells?’”

FBS’s proteins are specific to supporting the growth and development of calves. Since many biological pathways across species are conserved, Semper wondered if it was possible that cows and fish shared the same protein growth factors. To find out, he compared their protein sequences. “The idea there,” he explains, “was that if the sequences are very similar, then using bovine growth factors is probably totally fine.” But he found little similarity.

“Basically, fish cells are being told to divide by bovine growth factors. It doesn’t make a lot of sense.”

This compelled him to set out to develop a better way to culture fish.

The stakes for this research are high. Beyond sparing lives, reducing reliance on animal byproducts could deliver other considerable advantages for cellular agriculture. Industrial farming practices have sparked concerns ranging from disease outbreaks among livestock to farms becoming breeding grounds for antibiotic resistant bacteria. Quality assurance and scalability are yet another point in favor of serum-free media formulations, according to Semper. Every animal is different, so media that rely on serum derived from animals differ from batch to batch. Standardizing the recipe for a growth formula is essential to ensuring every cut of cultured meat or seafood is equally appetizing.

He is currently working to secure collaborations with industry partners to test his growth factors out on strains that might make it to market. “If the growth factors I’ve identified are offering improved performance over whatever they’re currently using,” he says, “that might help them either get better performance or reduce costs.” Semper’s optimism remains measured, and yet he can’t help but imagine the prospects of success. “It’ll be really, really exciting to see that first products come to market—not just in a controlled test environment, but actually subject to the free market when customers go into a store and make the choice on their own.”

To learn more about Cameron’s project, check out his project page.

This article was produced for New Harvest by Massive Science, a community of scientists telling fascinating, true stories about the science that’s happening now.