A year ago today, the White House told federal regulators that it was time to update the biotech regulatory system.

In the words of the White House, it was time to “initiate a process to modernize the Federal regulatory system for the products of biotechnology and to establish mechanisms for periodic updates of that system.”

(Modernize, indeed. Today biotech food products are regulated according to a policy document from the ’80s, which essentially says that the existing regulatory system (from the ’50s) can be made to work for biotech products).

The process began with three public meetings and is continuing with a high-profile study by the National Academies of Sciences, at the request of the USDA, EPA, FDA, and White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. The study (which excludes drugs and medical devices) will be released at the end of 2016.

I was invited to offer insights from the world of cellular agriculture to the study committee at a public meeting in San Francisco. It was an incredible opportunity to address some of the regulatory uncertainties that cell ag products could face in advance of having actual cell ag products in the regulatory pipeline.

(Side note: In case you aren’t familiar, cellular agriculture is the production of agricultural products from cell cultures rather than whole plants or animals. It includes products made from yeast, bacterial, microalgae, or animal cell cultures).

Here are the main points I set out to make:

1. Cellular agriculture is a neglected area of research (especially w/r/t tissue-engineered products like meat, leather, and organ meats).

Work in this field can address food security, public health, and environmental sustainability issues, but is not on the radar of big funding agencies (yet). This field is so nascent that even the basic research tools, like the relevant cell lines, have not yet been established.

As New Harvest is developing those relevant cell lines, we need guidance on what kind of data needs to be collected on these starter cultures.

2. Cultured products aren’t a new thing. Cultured commodities are.

There are already at least 58 products in the Code of Federal Regulations that are, or are derived from, cell cultures. They tend to be things like enzymes and vitamins, which make up a very small proportion of the end product. Cultured milk or egg proteins are different because they will need to exist at a commodity level, and they will make up the larger part of the product (aside from water). Does the current regulation suffice?

(Side note: The current regulation is called the Food Additive Law, and my guess as to why it’s stayed that way is because in 1958, when the law was created, new foods were mostly small volume things like colorants and preservatives — food additives. And therefore the law was not designed for brand new foods like cultured meat, for instance).

Further, what happens if we want to sell the milk-making live cell cultures themselves? How will those be regulated? Will they be considered processing aids, which help create the food product, but do not end up in the final product, like a food enzyme?

What about cultured meat? There is no precedent for the sale of tissues in current food regulations — do we look to the “D” in FDA for guidance? Can the cell lines be considered processing aids if they make up the bulk of the final product?

There is incredible need for regulatory clarity when it comes to cultured food products.

Not only will this help set a research and development plan going forward, it will also mean less hesitance from prospective investors injecting much-needed capital for scale-up work.

3. New Harvest is a future-consumer-supported research institute that believes in biotech business to make things better. This ain’t new.

More than consumer-supported, New Harvest is consumer-funded. It’s not novel for a non-profit organization to be advancing research that would ultimately lead to investment opportunities — cancer research groups do it all the time.

For research that is as high-risk, high-impact, expensive, and long term as biotech is, non-profits are crucial sources of non-dilutive, early stage funding.

After all, non-profits are part of the classic pathway from discovery to market for medical biotech. Non-profits were also crucial to creating high-yield crops as part of the Green Revolution. The model works, which is why we’re applying it to cellular agriculture.

4. Consumers are excited for cultured meat, milk, eggs, and more. Let’s label it!

The reason why New Harvest can be funded by 374 individuals (without a benefactor) is because we’re telling the story of cell cultured foods. The way they are produced — through cell culture — is what allows the products we’re familiar with to be more environmentally sustainable, safe, healthy, and humane than their conventional counterpart could ever be.

What’s exciting about cellular agriculture cultured products is the how they are made. Why wouldn’t consumers want to choose products made via a fundamentally better process?

Because of this, I propose “cultured” as a labelling term in the ingredient lists found on processed food products.

It would apply to the specific ingredients that are made in cell culture, which would include a lot of the 58 items I mentioned earlier that are already approved for sale.

(Side note: Those cultured products are also made via a superior process, because they don’t need to be made via chemical synthesis).

(Side side note: I realize we don’t know for sure that cultured foods will be literally a superior process, but all theory points in that direction so far. Much more research is needed, which is why that’s exactly what we’re funding.)

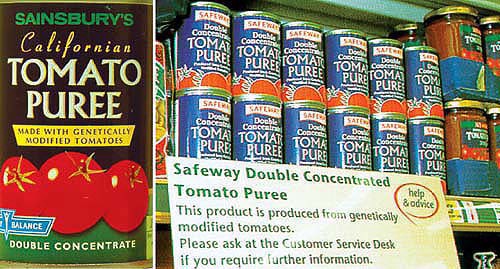

Let me point out that “genetically engineered” was not always a bad word. In fact, the very first genetically engineered food available for sale in Europe was a tomato paste made of genetically engineered tomatoes.

From 1996 to 1999, Sainsbury’s and Safeway customers could purchase genetically modified tomato paste. There was no legal requirement to label the product, but the company and the supermarket wanted to make sure consumers were educated. Curious consumers had access to leaflets describing the product, its benefits to the environment and consumer, and details of genetic modification and the regulatory process the product had to undergo.

The genetically engineered tomato paste was so successful that it outsold conventional tomato paste. That is, until 1999, when public concerns had the product pulled from shelves. I’d argue that it was because there wasn’t a concerted effort to label *all* genetically modified foods.

This story tells us that consumers want to know and want to learn about technology and its benefits — and will be happy to support food technology when it is indeed better.

We need to stop othering consumers as people who are fundamentally different than the people producing foods and food technology. We’re all consumers. We all care about what we’re eating. We also all care about supporting technology that’s better for the people and the planet. Let’s advocate for what we want as consumers rather than what the so-called “they” want.

(Side note: Jason Kelly of Ginkgo Bioworks wrote a great piece on GMO labelling in NYT which I highly recommend checking out.)

The National Academies of Sciences meeting was just the tip of the iceberg. It’s so exciting that our biotech regulatory system is changing, and that we’re part of it.

(Side note: I was shocked to hear that only ~50 members of the public logged in to see the livestream and only 10 signed up to attend in person. Given the volume of interest in biotech policy on the internet, why were so few present to proactively engage?)

We have a lot more work to do when it comes to working with government granting and regulatory agencies w/r/t cellular agriculture. But it’s snowballing, and these type of interactions will eventually lead to what this field needs more than anything — national support for early stage exploratory research.

I’m sure that meetings like this one will help New Harvest achieve the non-profit dream — to cease to exist — because the problem we set out to solve will no longer need our help.

✌️A million thanks to each of our 374 donors!✌️