Transcript

Also available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever else you listen to podcasts!

Alex (00:04):

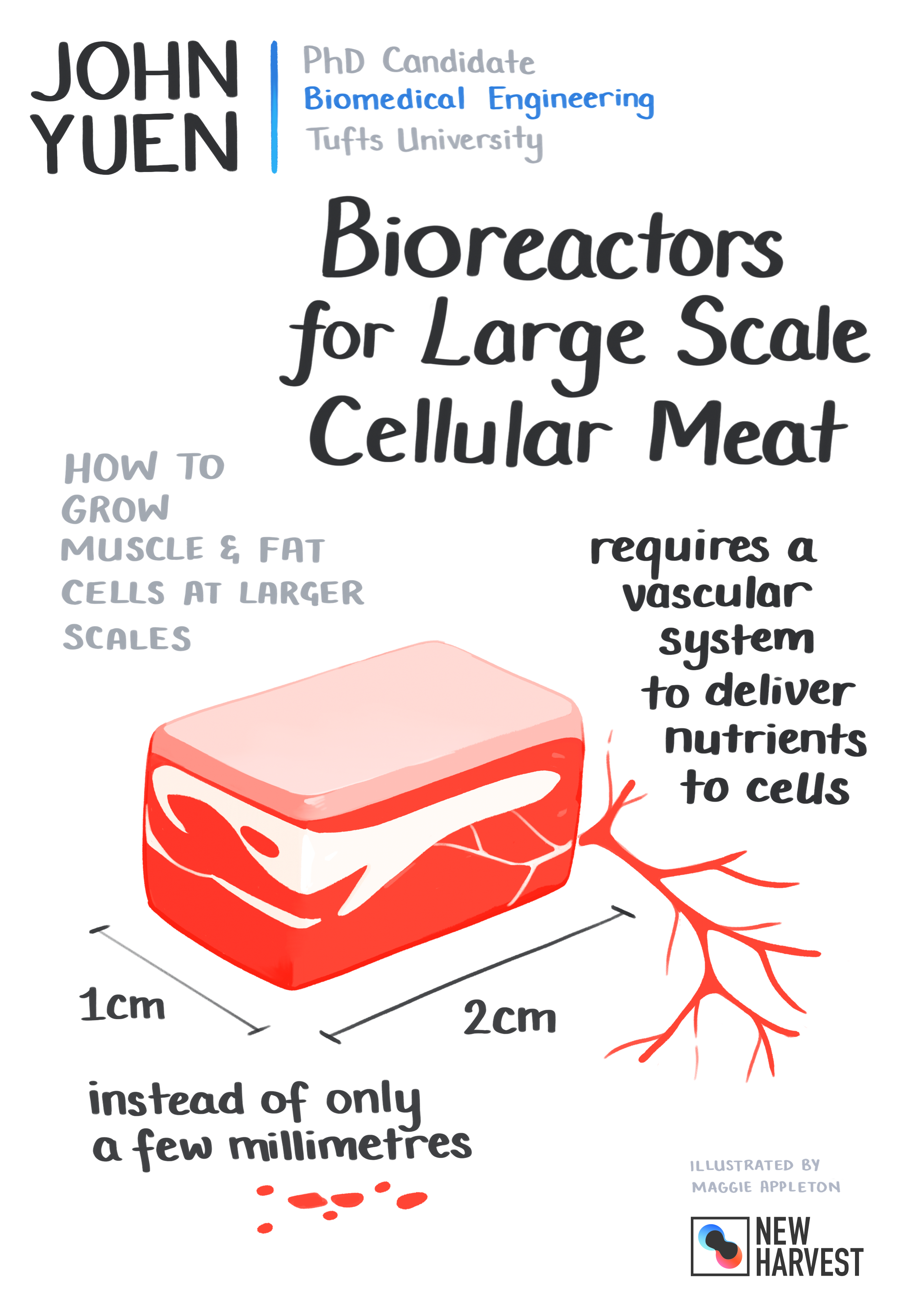

Thanks for joining us on the cultured meat and future food show. We’re excited to have John Yuen as the gue

st for today’s episode, part of the New Harvest Fellowship series. John is a fourth year PhD candidate working on cultured meat in the David Kaplin laboratory alongside Andrew Stout, Natalie Rubio, Ning Xiang, Michael Saad And Sophie Letche – a growing cell ag team. John’s goal is to develop scalable techniques to overcome the challenges of oxygen and nutrient delivery to cells within larger tissues. For example, it’s often quoted that cells can only survive about 200 microns away from a blood vessel or other sources of nutrition, such as cell culture media. This means that even a one millimeter thick tissue might encounter cell viability or survival issues within the core central region. To address this, John is investigating methods to generate macro scale constructs of muscle and fat via perfused, 3d tissue culture strategies.

John (01:01):

The hope is that methods to support cell survival and larger constructs will enable more advanced muscle and fat tissues to be grown in the future, containing the higher order, macro scale structural organizations seen in products such as full cuts of meat. Imagine the large arrays of align muscle fibers seen in steak or chicken breasts, et cetera. I had a great conversation with John and I’m excited for us to jump right in. Let’s go.

Alex (01:29):

Thanks for joining us for the Cultured Meat and Future Food show. We’re excited to have John Yuen as the guest for today’s episode. John, I’d like to welcome you to the Future Food show.

John (01:39):

Hi, excited to be here and maybe a bit apprehensive, but I’m excited.

Alex (01:44):

Cool. So tell us a little bit about your background and also when you first heard about cultured meat.

John (01:50):

I did molecular biology during my undergrad, and I worked in an in vitro bone lab where we were trying to recreate bone tissue or the bone being hydroxyapatite, mineral, and collagen, but without the cells. So it’s cool that I moved from in vitro bone to in vitro meat. And with regards to how I heard about cell cultured meat, I had a professor that had us go to these seminars and a lot of them were about the environment or social responsibilities. So that first put me into a more environmental mindset when previously I just didn’t think about being green at all. But then with that mindset, one day I was just laying in bed during spring break. I was just wondering what I would do with my life, because I was nearing the end of my undergraduate career. And I just suddenly thought if meat is just muscle and fat tissue, why don’t we just do it with cell culture, then we don’t have to kill all the cute animals. And then I thought maybe I’m the first one to think of this. I’m going to be famous. So went on Google and searched it. And apparently it was something that was already being done. So I was like, ah, okay.

Alex (03:06):

And what year was that, actually, that you were thinking about this?

John (03:09):

Maybe 2016, I think

Alex (03:12):

Early days, definitely after the Mark post burger, but early days compared to all of these cultured meat companies popping up.

John (03:20):

Yeah. Yeah. It seemed like I could still, of course now anyone can still contribute, but I just thought, okay, I didn’t think of it, but perhaps if I try and do my PhD in something related, I can help out somehow, help make it a reality, essentially. So then I searched online. I thought that I could just contribute somehow by doing the PhD in something related, that idea was of course inspired by finding New Harvest, which at the time was really like the main source, an active group on cultured meat. And then I saw that they had a PhD program with the David Kaplan laboratory at Tufts university. So I just applied to Tufts and got in. And that’s how I got to where I am now.

Alex (04:05):

Wow. That’s cool. New harvest is still one of the leading resources out there. That’s interesting because I think when I started looking into cultured meat, of course, New Harvest popped up as one of the first things. And I think it was also a marketing and promotion around Paul Shapiro’s, clean meat book and a lot of stuff about New Harvest, but specifically the graphic that new harvest created with a yellow background. And I think that graphic is still being used so often to describe the cell culture process. Tell us if you can, the specific details of your research in the Kaplan lab right now,

John (04:45):

First as a side note, the graphic really reminds me of Nike, the story of the Nike logo about how they just paid someone like a little bit to make this logo. And suddenly it’s this huge thing. Maybe they should pay the creators of the graphic, but I guess like New Harvest is a nonprofit.

Alex (05:04):

Oh, I know. I wonder who did create that graphic back to that Nike story. I think they went back to that Nike designer and gave that person like a million dollars of stock. Is that right? Did you hear that too?

John (05:15):

I don’t remember too clearly, but yeah, I think something like that happen. Back to the research, at first I focused on extending cell proliferation through non-GMO means, not that I have anything against genetic modifications, but just since it would be in line with what the market may demand. And then I eventually transitioned now to working on bio-reactors for perfused tissue culture of macro-scale constructs of muscle and adipose. So that being like big constructs, something tangible, something you can hold and pick up instead of like tiny pieces of muscle and fat. My goal is to make bigger pieces and then to make the bigger pieces, I’m trying to deal with the issue of nutrients, oxygen reaching the inside of these larger tissues, because otherwise, without, for example, in our body vasculature or blood vessel system or something to replace it, the cells on the inside will just die.

Alex (06:17):

So there are a lot of different bio-reactors that are used. What kind of bioreactors are you looking at or potentially even designing through your research for kind of these bigger pieces?

John (06:28):

So I suppose there are different key aspects. Key concepts. One is naturally to vascularize the tissue. In tissue engineering, that’s of course a goal, but it’s still something that’s difficult to achieve. So one aspect that I’m working on is to develop techniques, to grow a vasculature within whatever tissue you’re trying to generate. So i.e. having a piece of muscle tissue that also has capillaries in it, so that nutrients can be delivered to the inside. Another aspect is just for example, having a piece of muscle, but also have like tubes running through it so that the media can just physically inherently reach the inside of the tissue.

Alex (07:12):

And so how far along is this research? So I guess in a simpler way to ask, are we able to vascularize cultured muscle and fat and have we gotten there? And if so, I guess to what extent and what is the metric for measurement?

John (07:29):

There has been a lot of work on generating vascular networks, capillaries, usually either by itself. So we can get, for example, hydrogel with a really nice developed capillary network inside. And I haven’t looked much into other tissues like nerves and stuff like that, but for muscle and fat, there’s a lot less work on growing muscle with the endothelial cells i.e. blood vessel cells or fat with the blood vessel cells. But there has been some work on it. Very cool work. For example, Professor Lieven Thorrez with the first author Dacha Gholobova they did work on capillaries in muscle. And then they show that that immunofluorescence images of the muscle that they create outside the body in vitro there’s muscle, but then also vessel networks within it. And then there’s also the Brey lab with the first author Feipeng Yang, where they optimized a system for generating fat with blood vessels.

John (08:29):

But to my knowledge, there isn’t much more than a few of these works here and there, but of course they’re very great works. The other thing is that these are all small scale pieces of tissue. So I want to do what they did, but for big constructs of tissue. And that would involve doing things like coupling that kind of system with a bioreactor to support a bigger piece of tissue. Or something like combining the vascularization with channel perfusion and things like that to enable a bigger construct. So that’s the state of the field at the moment, as I know it, hopefully I’d, haven’t missed any key pieces of literature. And then with regards to measuring vascularization, you can do immunofluorescent staining for markers, such as VE-cadherin, CD 31, which are proteins expressed for the most part by endothelial cells on their cell membrane. So if we have a piece of muscle or fat tissue, hopefully vascularized, we can look for the cells that have those proteins being expressed on the surface and be like, okay, the blood vessel cells are here and then you can use that to track and see if there’s a network vessel shape and see if the staining is also like circular if you look at a cross section, because that shows that there’s like a tube being formed. And you can also perfuse in compounds, fluorescent compounds, such as beads or molecules, such as dextran. And if you insert it into the system, you can image the fluorescence and see if it tracks the blood vessel and network to show that it’s flowing through the network and that there is a network for it to flow through, instead of it just diffusing through the tissue completely evenly, generally like through the tissue. So those would be some ways to measure vascularization.

Alex (10:11):

When you’re talking about bigger pieces, what would be considered a big piece?

John (10:16):

For the lab scale, where we’re just doing proof of concepts where we’re focusing on basic science? I would say that macro scale to us is on the centimeter scale, like a few cm by a few cm or even one cm by one cm, just to demonstrate something that could potentially be scaled up even further just because of cost and effort. So not that amazing, but still something that is going from something really tiny, a few millimeters to something that you can actually pick up and hold comfortably between your fingers.

Alex (10:45):

Wow. Okay. Yeah. That’s definitely bigger than I expected. That is pretty big actually. So that’s cool. When you hear blood vessel networks, it’s hard not to think of the work that’s going on in the Gaudette lab and Jordan Jones. Are you collaborating with their team or Jordan Jones, who’s also a New Harvest Fellow? Are you collaborating or is it a different research set?

John (11:09):

My project specifically, it’s in a different realm, but I definitely think that those are very promising avenues for dealing with the problem of vascularization slash just delivering nutrients to the interior of tissues. And we have a one undergraduate Julian Cohen working on a cellular space project with Ning Xiang, our meat post-doc, and they communicate with Jordan and get some of the plant tissues from Jordan Jones. So that we do on the lab scale have communications and collaborations.

Alex (11:45):

Cool. So you mentioned that you changed your focus area of research. What was the main for that shift and how was that process? Did you have to actually start your program from scratch or was it a smooth transition?

John (12:01):

So essentially I was working on two projects broadly at once. One was the cell proliferation stuff, and one was the vascularization bioreactor stuff. And during my stage of the PhD where you have to come up with a concrete research plan for the rest of your time, there at least that’s how it works in the Tufts biomedical engineering department, Professor Kaplan said that it’s best if I focus on one of them, at least for the presentation. And then I gave my presentation and I was advised to just narrow my focus to just one of the two main projects that I was working on at the time, just so that I like achieve enough on any one side. I guess like Sun Tzu’s Art of War. You don’t get too spread out thin just so that I can focus and get some achievements on something. So that’s why I ended up focusing on one. And then on the New Harvest website, it talks about the cell proliferation stuff because I originally applied with that project. But one of the core tenants of New Harvest is that they try to support people, not specific projects. They’re okay if you need to switch to something else, because they’re trying to develop the person.

Alex (13:15):

I can’t believe we’re 70 episodes into the podcast and this is only the first time somebody has referenced Sun Tzu’s Art of War. So I’m glad you did.

John (13:23):

Nice. I wanted to also mention that another factor is likely that I wrote a grant with Dr. Kaplan and we applied using the bio-reactor project. And then we got the grant. So that of course is another factor that would have influenced things. So it was exciting because as we mentioned, government support for cultured meat projects in research is sparse. So we were really excited to actually have like funding for the research that the cultured meat research that we were doing in the Kaplan lab.

Alex (13:57):

Cool. So it wasn’t such that you did a 180 transition, it was more that you just isolated your focus. And so that’s great. Can you tell us a little bit about some of the others doing research in the Kaplan lab and has there been a special sense of community within the graduate studies? And I’m really mentioning this because it seems like the Kaplan lab is quite famous in the world of cellular agriculture.

John (14:21):

Yeah. Other than Natalie Rubio, Andrew Stout and I who have been on the podcast, we have two new PhD students, Sophie Letche, who’s also a New Harvest fellow now and Michael Saad who used to work at Perfect Day foods. And they’re like really great to work with motivated. And I think that’s something cool about the meat PhDs because it’s people seeking out deliberately because they want to come do this research. So then everyone’s like really into it. And then we also have a lot of undergraduate interest, especially when they hear about this research from the cellular agriculture course that we’re teaching. We’re teaching a completely remote one this semester because of COVID. So we get a lot of very interested, motivated, undergraduate students to help us out in the lab. And then altogether it’s a very good vibes community because everyone’s motivated to be there interested in the research.

John (15:21):

It’s very synergistic. We’re able to help each other a lot, all the time, bounce ideas off of each other. Just be friends. So it’s very valuable in that sense. Oh, and then we also have our post-doctoral scholars, Ning Xiang, who used to work for a while at Just so she has some experience in that area. And then we have another postdoc who’s like dabbling a bit in the meat research, Sophia Theodossiou. But yeah, there is a sense of community between all of us, I think, because everyone tends to be fairly into whatever we’re researching and it’s like a very fun time, happy time. I think I’m just going on and on.

Alex (16:01):

No, that’s great. How long is your PhD program and what are your plans after PhD? Have you thought about starting potentially a new cultured meat company or perhaps joining one?

John (16:13):

I haven’t thought about it too much because I’m mainly trying to make sure I get achievements here now, but I’ve been just thinking about it broadly a little bit. And I think some options potentially are doing a post-doc. Are you working in another lab for awhile? Just because I would be interested in learning more skills. For example, I was like looking at the Bursac lab at Duke. I’m not saying they’ll accept me, but they’re like big players in skeletal muscle tissue engineering in general, especially for medical applications. So it’d be really cool to go and learn from the greats. And then on the other hand, like for example, professor Helen Blau’s lab at Stanford, the papers are like usually very high quality and cover all the bases in terms of providing the reader with the necessary data. And then they work on things like really cool technical things like mRNA delivery, which I feel like would be relevant to the cellular proliferation project that I focused on in the past, places like that. But also I’m down to just do applied research in a company, things like that. Whichever is cool. Whichever is fun, whatever pops up since there’s still some time before I’m actually out.

Alex (17:30):

And I had a question here about how can the research you’re doing impact the cultured meat industry, but there’s so many ways it could impact the cultured meat industry. Not only from just like stepping stones and research, potentially really amazing products. And so I guess with that, I’ll kind of transition into what are some of the insights in the cell ag industry that we’re not talking about, but we should be talking about more often?

John (17:58):

I hope this doesn’t end up being too long, but I suppose people do talk about this. But some things such as cultured meat has been learning a lot, taking a lot from the medical world of tissue engineering, et cetera, and applying it to cultured meat, but perhaps soon we can pay it forward and help the medical industry. For example, if we develop techniques to make bigger tissues, it could come back and have applications in the medical world. For example, if you can make big pieces of muscle that can help people with volumetric muscle loss, i.e. where they lose a lot of muscle, which includes losing the parts of the muscle responsible for regeneration, so it can no longer repair itself. Maybe in the future, we can just put a piece of muscle back in already vascularized, once it hooks up with the innate blood vessels, it’s ready to go.

John (18:50):

If we can make macro-scale fat tissues, then that has applications with soft tissue defects, plastic surgery, for example, or reconstructive surgery, where in this case, instead of losing muscle, just some random like tissue. So you can fill that with fat. Whereas at the moment, for example, people use graft of fat from somewhere else on the body. Maybe in the future, you can just put some fat in instead of having to take it from somewhere else in the body. If we can make vascularized skin, we can maybe save someone’s life with skin grafts. If they get burned for example, and they have no more skin to graft from somewhere else to seal the body, maybe you can save someone’s life. If you’re able to produce living vascularized skin tissue at a large scale, maybe we’ll make it even cost-effective for the people that are in trouble.

John (19:40):

So that’s one thing. Another thing is I think that we may be farther off than we think from getting everything produced at scale in terms of cultured meat at scale and at a low cost. That was the techno economic analysis recently by Dr. Humbird. I forgot his full name. That is a super deep dive into how cost-wise, it may be challenging to get cultured meat production done at scale at a low cost. So I think that’s another thing that we should talk about more, but then it fits within my maybe more personal view that things will become more viable once we get new technologies pop up that enable lower cost higher scale production. And that at the moment we should focus on that. But then of course it’s possible that the companies have solutions to that at the moment that we just don’t hear about too much.

John (20:34):

And I’m sure they’ll eventually talk about it because eventually they sell their products. They would want to show that it’s environmentally friendly and they would want it to be low cost. So maybe they’ll come out in the future with their own techno economic analysis with their production process and then show us how it can be done at a low cost at a low impact to the environment. So essentially what I was trying to say is something that’s not often talked about is how it may be quite difficult, technologically, to create cultured meat at scale at low cost, with evidence being something like the Humbird techno economic analysis, but then it’s kind of a depressing analysis, but I think there’s still hope mainly because a lot of the information available for making these analysis, maybe just not in the public domain, something further I have to say about this is that, and this doesn’t necessarily mean that the industry is dead until a few decades later in the future or anything once we have a lot of technological development, but I think in the meantime we have things like we may be able to get really compelling products out. For example, with just large scale cultured fat production, since a lot of flavor from meat comes from fat, we may be able to combine plant hybrids or plant proteins that are very convincing, for example, like the Impossible burger and just add cultured fat in which should be a lot easier to make at scale to get that taste aroma essence of the flavor of animal meats. And then that may be already really compelling and much better for the environment. And you don’t have to kill the animal and things like that.

Alex (22:13):

Absolutely. I think you’re right in that even differentiating between different types of meat, you get that flavor profile through the fat. And so hopefully we do start seeing more of that as cell cultured meat or cell cultured fat becomes more common in the realm of food. Definitely very exciting stuff. And I think it’s refreshing to hear that once we do have more data, then maybe from economic standpoint, things will start looking not only more optimistic, but also more solid because I think a lot of those reports, like you said, they’re using the limited data that is available now.

John (22:52):

Yeah. And apologies being all over the place with answering that. I felt like, I guess I haven’t like actually put a huge amount of thoughts into this issue, but it’s just things that are on my mind.

Alex (23:03):

No, I think that was great because I think if we were thinking about it all the time, I think we would be talking about it more too. So maybe this will be the catalyst to get people to start thinking about these things more often. Maybe even a new plant-based food company that uses cell culture fat. You don’t know! You can get in touch with John through New Harvest and learn more about new harvest www.new-harvest.org. John, do you have any last insights for our audience today?

John (23:31):

I think safety concerns will come up in the future and maybe the best way for you to find out if it’s actually safe or not is to, at least this is with regards to ingredients is to read for yourself generally recognized as safe documents that are publicly available. For example, for allulose, the sugar replacement, for EPG, the fat replacement, people are always wondering about the safety of those. The FDA documents are actually online and available for you to read the evidence that’s being provided for its safety. So if you’re ever curious, you can just look it up yourself and read. Of course, I don’t know if there’s a bias to those documents since it’s submitted by the company, but perhaps that’s just the way of becoming a bit more informed.

Alex (24:18):

Cool, great. And that’s definitely great insight because as we know GMOs, for example, people do like to jump to conclusion, John. Thank you so much for being with us today and sharing your insight on the Future Food show.

John (24:31):

Very glad to be here. It was quite fun.

Alex (24:34):

Cool. This is your host, Alex, and we look forward to being with you on our next episode.

Transcribed by New Harvest volunteer Bianca Le.

To stay up to date on New Harvest research updates and events, sign up for our newsletter.