Transcript

Also available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever else you listen to podcasts!

Anita (00:19):

Hello and welcome to the Cultured Meat and Future Food Podcast. My name is Anita Bröllochs. I’ve been on the Cultured Meat and Future Food podcast since the first episode, but I’ve been working in the background most of the time. I am pleased to be the host of today’s episode. This podcast episode is part of our New Harvest Fellowship series and it is our first podcast episode in German.

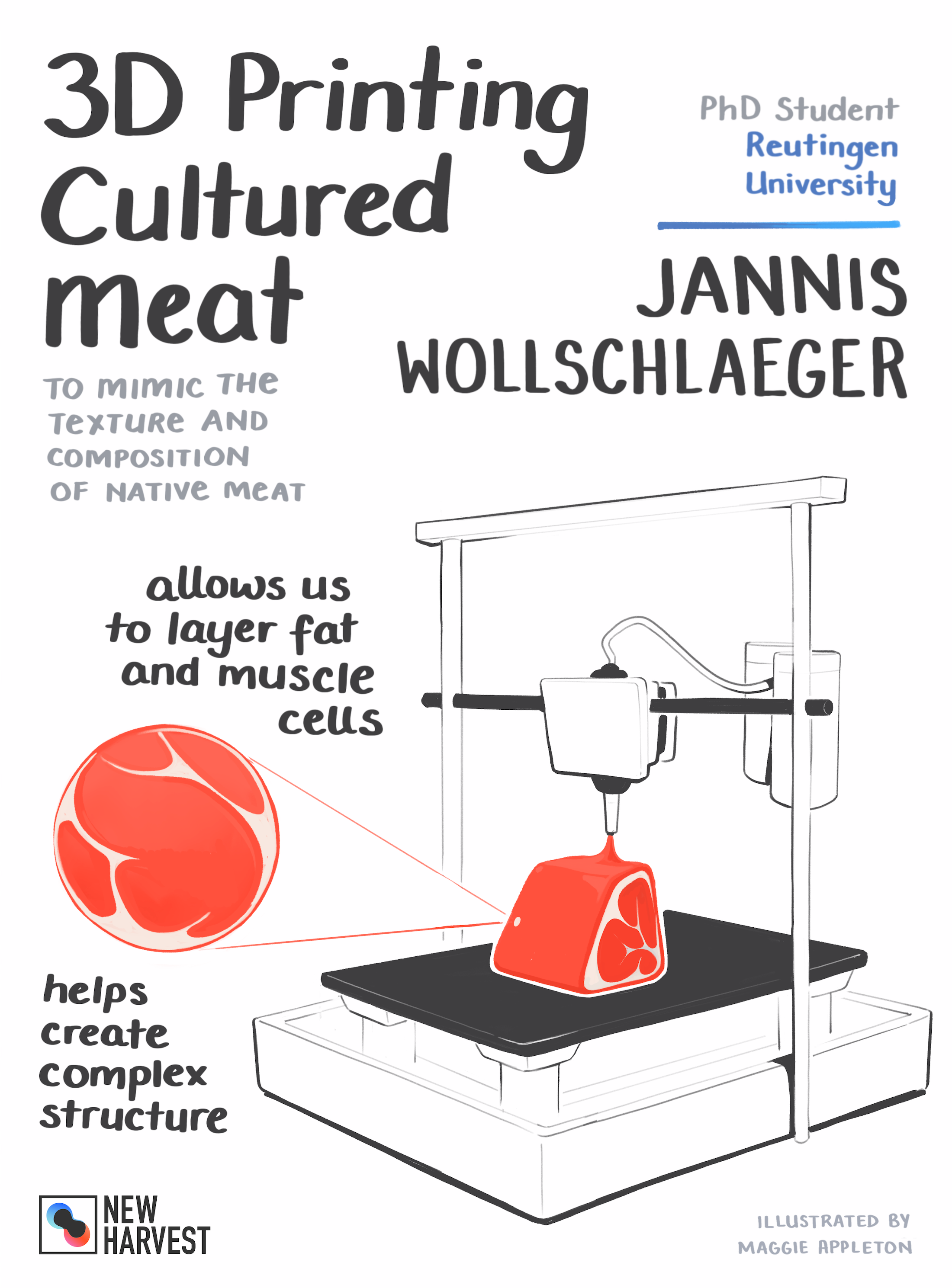

We are happy to have Jannis Wollschläger as a guest on the podcast today. Jannis completed his Masters in Industrial Biotechnology at the University of Ulm and the University of Biberach at the beginning of last year and has been working on his doctorate at the University of Reutlingen since September 2019. For his project, he is working on the development of a defined, inexpensive co-culture medium, animal-free bio-inks, and a simplified CAD model of the natural fat and muscle tissue structure for the production of meat in the laboratory, or more precisely, for the 3D printing of meat in the laboratory. Jannis also received a scholarship from New Harvest in December 2019.

Jannis, welcome to the Cultured Meat and Future Food Podcast.

Jannis (01:40):

First of all, thank you for inviting me, I am looking forward to the next few minutes and hope that I can bring cultured meat from the laboratory a little closer to the audience today.

Anita (01:48):

Great, we are very happy that you are here. Can you introduce yourself briefly and tell us how you came to New Harvest.

Jannis (01:57):

My name is Jannis Wollschläger and I’m doing my doctorate at the University of Reutlingen. I started my PhD in September 2019 and my PhD project is funded by New Harvest. I came to New Harvest through college. I had applied for jobs in tissue engineering in the medical field, but they then suggested to me whether I should apply for a scholarship at New Harvest, which involves making meat in the laboratory and doing research on it. This was interesting for them because it enabled them to expand their range of research work.

Anita (02:40):

Have you ever heard of cultured meat or was that something new for you?

Jannis (02:45):

That was actually something new for me, I had not heard of it before. But if you read into the topic, it is totally exciting and I think it is also a very important topic for the future.

Anita (03:04):

And your project is ‘Meat 3D printing’. For listeners who may be wondering what that means, can you please explain what it means to print meat 3D? And can you explain it as if you were explaining it to a 5 year old child?

Jannis (03:25):

If you start from scratch ‘How is meat structured?’, it consists of different types of tissue such as muscle tissue, fat tissue and other types of tissue. These types of tissue have different functions in our body and also in the body of animals. Meat mainly consists of muscle tissue, which is relatively complex. To reproduce that, you would need to 3D print it.

So why would you want to 3D print it at all? Why can’t you just get the beef or pork steak out of the counter as usual? The world population is currently growing extremely quickly – we are about to reach 8 billion inhabitants and that will continue to increase. With current conventional meat production, i.e. with cattle, pig, poultry, we won’t be able to continue meeting the demand for meat. The main drawbacks with conventional cattle breeding are that a lot of land is required and it requires high energy and water consumption. Over time, we simply cannot cover this with the resources of our earth. Greenhouse gas emissions are also relatively high, and for vegetarians, vegans and animal lovers in particular, factory farming is also linked to ethical problems. So we want to create alternatives, and one of these alternatives is to produce meat in the laboratory. Since meat has these complex structures from the various types of tissue, you can try to recreate them using 3D printing in order to imitate the structure as closely as possible from that of natural meat. That’s why we take this approach to 3D meat printing.

Anita (05:36):

So what exactly are the advantages of cultured meat? Do you need less resources, water and energy? What exactly would be the advantages if you could produce this meat on a large scale?

Jannis (05:51):

So the first big advantage is that you need much, much less floor space to produce this meat. Conventional cattle breeding requires a lot of arable land to produce cattle feed, and 70% of the world’s arable landscapes alone are simply used to produce cattle feed. If you then no longer needed this land area for animal feed, you could also use grain and other vegetables there for human consumption – this is a big advantage. According to projections, it should also consume significantly less energy and water, because these animals need a lot of resources to survive. And all the transporting involved with meat production requires a lot of energy. If you do all of this in the laboratory, or if you later produce this meat in larger reactors, it is simply more efficient. In the same way, fewer greenhouse gases will be emitted. What you also have to consider is that the larger the animal you want to eat in the end, the more efficient it is to produce the meat in the laboratory. That means, for example, that making a beef steak in the laboratory will ultimately save more resources than those involved with making chicken.

Anita (07:26):

And would the result of the 3D printed meat be exactly like meat or would it be different from the meat that we know today?

Jannis (07:36):

At this stage, using current approaches, you can mainly produce burger patties and minced meat because they don’t require recreating such complex structures. This means we can recreate meat that has already been processed. But the goal is to eventually develop a 3D printed steak that has the same taste, consistency and appearance as steak from a cow, for example. However, we need to do a lot more research before we can reproduce this structure. But I believe that it will be possible. And what will also be possible with 3D printing is that meat can be customized. That means you can choose what your meat could look like. There is also the possibility, for example, to incorporate your own ideas and to design completely new food, which is called a ‘novel food’ in English, which is unlike anything we currently have available at the moment.

Anita (08:49):

Some also talk about the fact that one could then theoretically also produce half chicken, half pork, hybrid meats.

Jannis (08:57):

Exactly, that would also be conceivable with perhaps completely new flavors that could come out of it

Anita (09:08):

Exactly. It all sounds very exciting. And do you work on your project alone or do you work with others in your team?

Jannis (09:16):

When I started, I was the first to deal with this topic. Before that, the expertise and knowledge was primarily on human fat and skin tissue, which then goes more in the medical direction. The same techniques are used, so you can transfer the knowledge that is already there piece by piece, but they use human cells and I use animal cells from pork and beef. And now it has been a few months since I started and the Cultured Meat Group at Reutlingen University is starting to grow. That means another PhD student started on the meat project last week and we now have three postdocs who support us, and I still have a student that I supervise, and there is another intern who works with us on this project.

Anita (10:32):

I can already imagine that there are many challenges when trying to transfer the techniques from human cells for medical purposes to meat production and that there are many things to consider. What are the biggest challenges you see so far and what are the next milestones for your project?

Jannis (10:54):

So let’s start with the question ‘What are the challenges when trying to transfer the techniques for tissue engineering in medicine to meat production?’. On the one hand, costs aren’t too big of an issue in human tissue engineering for regenerative medicine purposes, however it is a major challenge for cultivated meat production.

Other challenges include recreating the complex structures of different tissue types. In addition, you have “organic inks” in 3D printing, which contain these cells of interest. This means that the organic inks contain muscle cells for muscle tissue and fat cells for fat tissue, which can be used to 3D print meat. And these bio-inks do not only consist of cells, but they also have a support material around them which is also called hydrogel. These hydrogels are jelly-like, much like gelatin or Alignat, which are well-known hydrogels found in the kitchen. These hydrogels must be edible for humans but also support the growing cells.

We are working with animal cells for the first time in the laboratory, so the focus is on cell isolation. That means I am currently isolating muscle stem cells and fat cells. We want stem cells because these cells have the ability to continuously multiply. Once the cells multiple to the point where they reach the desired mass, we can then differentiate the cells. Differentiation means that they transform into a specific tissue type, such as muscle. I am currently working on isolating the stem cells and on improving this isolation. Later I would like to co-cultivate stem cells from adipose tissue and muscle tissue together. Cultivating means that they can grow together in one environment without hindering each other. And for this you also have to develop suitable media that contain the nutrients that each cell type requires in order to grow. These are the next steps before this 3D printing is even in the room.

Anita (14:17):

Then where do you get these tissue samples for cell isolation? Are they from a live animal or from a dead animal?

Jannis (14:29):

Ideally, the animal does not have to die for this. Biopsies can be taken from the animal and then it lives on. You only need small amounts, a few grams. This means that the animal is not harmed much. However, you need research animals in the institute that can be used for this. Unfortunately, we don’t have these here in our case at the university, so I get tissue samples fresh from the butcher. That means immediately after the slaughter, I can pick up what is left and I then isolate the cells fresh from the dead animal. However, we will need to find alternative methods for mass production. The reason I get the butcher’s samples is that it was the easiest source to start researching and there are no alternative sources of live animals in the immediate vicinity.

Anita (15:34):

And did you ever tell the butcher what you used the tissue samples for?

Jannis (15:39):

I always asked if they were ready to provide me with fresh tissue samples. So far, all butchers have been very cooperative and so far there have been no problems. So far, there have been a couple of questions from time to time as to what I want to do with the samples. In the first step I just said that I would like to isolate these stem cells and then examine them for more. I did not mention that the idea behind it is to produce meat.

Anita (16:09):

It would be exciting to find out what the butchers think about it.

Jannis (16:12):

You also have to consider that this cultured meat will not replace a butcher in the immediate future. There will probably still be butchers in the future and it will not be completely switched to cultured meat in the next 50 years. First of all, more research in the field is still required and consumer acceptance has to be established. There will certainly be consumers who say they would like their piece of meat from a butcher. Therefore, cultured meat is more of a competition for factory farming. The butchers I asked for are small butchers who want to cause unnecessary harm to the animals, and of course the consumers don’t want that either.

Anita (16:57):

There is also a question from Alex – and Alex is usually the host of this podcast. His favorite food is pork knuckle and he would like to know if you can imagine a future in which we might one day eat 3D-printed pork knuckles.

Jannis (17:17):

I actually don’t think that is so unrealistic. If we now go through the steps, the simplest would be minced meat, then things like steak or schnitzel and then the pork knuckle would be even more complex in terms of structure, since there are other types of tissue in pork knuckle, such as the bone and also the skin. But most of the time, the bone is not consumed, so it might not be necessary to cultivate it in the laboratory at all, and maybe you could use some other support structure that imitates this bone but has no living cells. That would simplify a lot and you could then print the other types of tissue around this bone. I could imagine that it will be possible at some point.

Anita (18:12):

I think he will be happy! I also believe that muscle cells always need anchor points to hold on to. And maybe this bone structure would be very practical to then print the cells on it.

Jannis (18:31):

That’s right, you could definitely combine it to support the muscles in this situation so that you have these anchor points at which the muscle cells are stimulated to grow. This is definitely conceivable.

Anita (18:51):

I’m curious to see if we can experience that. And we mentioned earlier that 3D printing for cultured meat can be very versatile and it offers many possibilities. And to address another topic, do you think that 3D printing could also be used in the production of vegetable meat alternatives?

Jannis (19:23):

The interesting thing and in fact, this technology is already being tested in this area, which is currently very trendy. There are already startups that deal with this, for example, Novameat or Redefine Meat, who want to print meat with vegetable proteins. So work is already underway to further optimize the existing vegetable imitations.

Anita (19:57):

We generally see a lot of activity from the cultured meat industry from the USA, the Netherlands, Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, Israel, etc. But what about Germany? Is Cultured Meat an issue in Germany right now and what is the current situation? Is interest growing?

Jannis (20:39):

This is definitely an exciting question that you naturally deal with when doing research in this area. What about in your own country? And as you have already noticed, I have often said ‘Cultured Meat’. There aren’t even many good translations for Cultured Meat at the moment. Most of what comes up is ‘laboratory meat’ but otherwise English terms are actually always used, which already shows the problem that in Germany the trend that is currently in progress is being missed. All of the startups are outside in the USA, the Netherlands, Israel and Germany. Last year I was at the Cultured Meat Conference in Maastricht, where Mark Post was also the host, and we were the only research group from Germany that dealt with this topic. But what I found out is that reporting on the subject is increasing in Germany, which is a good first step. So more people in Germany are becoming aware of this research area. Eventually, this will lead to more awareness and growth of the field over the next months and years. In Germany, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, a large company that supports Cultured Meat, does support startups abroad. However, I also think that there will be more startup activity in Germany in the next few years.

Anita (10:28 pm):

I also find the name of Cultured Meat, which you mentioned, very exciting. We even had countless names for it in English: Cultured Meat, Clean Meat, In-Vitro Meat, Franken Meat, … We really had 50 different names. If any of the listeners has a good idea for a German name, let us know because we definitely need a good German term for it. I don’t know if you know the book by Paul Shapiro, but it has now been translated into German and the title is ‘Clean meat’, which in my opinion sounds a bit like meat cleaner.

Jannis (23:12):

Yes, with the English terms alone there are already whole studies on how to call it and what the population thinks of it in different countries and even there you can’t really find the denominator. This is definitely a point that should be clarified, because if you have a good, catchy term for it, then you can promote it better. That is why it is an important point in terms of consumer acceptance that should gradually be addressed.

Anita (24:07):

That is definitely very exciting. Jannis, is there anything else you would like to share with our audience today?

Jannis (24:14):

In any case, I would like to thank you very much for listening in, one aspect of a scientist’s work that is often left out is how to communicate with the general public. Therefore I am glad that you, Anita and Alex, have given us the platform, that I can simply pass on my knowledge and thoughts about this topic.

Anita (24:49):

And if someone wants to get in touch with you, how can you best be found?

Jannis (24:52):

Just Google ‘Jannis Wollschlaeger’ in combination with ‘Hochschule Reutlingen’ and then you will probably find me. And I’m also on LinkedIn.

Anita (24:57):

Great! Jannis, thank you for being our guest today and for sharing your experience with us on the Cultured Meat and Future Food Podcast.

Jannis (25:04):

Thank you. Thank you very much and bye!

Anita (25:09):

Thank you very much for listening and we look forward to seeing you again on the next episode!

Transcribed by New Harvest volunteer Bianca Le.

To stay up to date on New Harvest research updates and events, sign up for our newsletter.