Your background is in heart research. How did you get interested in cellular agriculture and pivot to growing meat from growing organs?

I started out my PhD growing primary cardiac cells. I essentially wanted to grow hearts in a jar and have an ex vivo cardiac transplant system. Trying to get the best cardiac tissue growing is what led me to cell ag.

My whole scientific career I’ve been obsessed with cardiomyocytes—it’s my favorite cell—but while the basic biology of cardiovascular genetics has sustained my interest, it has been hard to feel like I’m really doing something important. I would love to grow an entire heart for transplantation. Will that happen in my lifetime? Maybe. But I’m 31 at this point. I want to use all of this knowledge to solve a problem, to grow a tissue that meets a need in society right now.

I like cell ag because it can apply this science to address food security. Along the way, it’s developing tech that is going to inform a lot of basic biology that brings us a few steps closer to growing a heart.

You are the first person to ever apply for our dissertation award. Why did you apply?

One of my rotations at Tufts was with a gentleman who was collaborating with Dr. Kaplan, using the silk he makes to grow cardiac cells. That’s when I learned about [New Harvest Research Fellow] Natalie’s work. I was jealous that she was doing a whole dedicated PhD about cellular agriculture, which I didn’t even realize was possible until I was wrapping up my own PhD. That’s when I saw the funding opportunity on New Harvest’s website which would allow me to spend this last part of my PhD orienting my research toward cultured meat.

What research will you be doing with this grant?

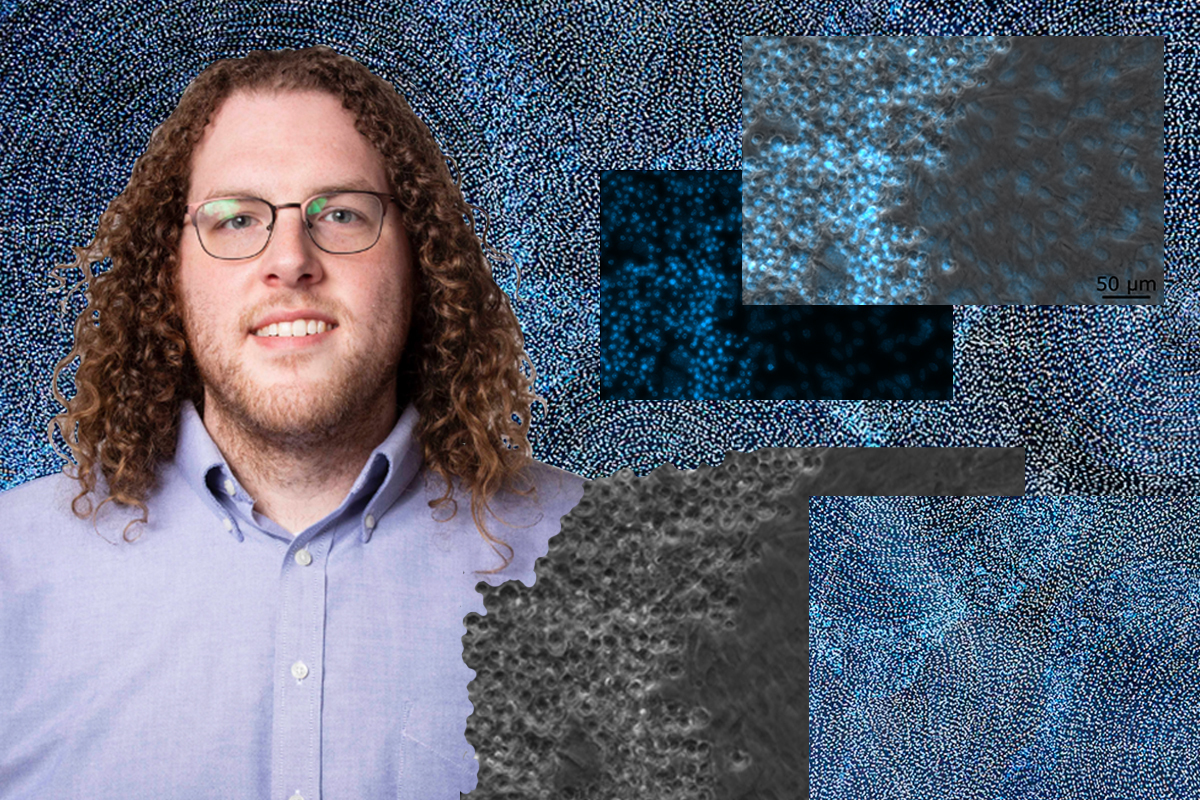

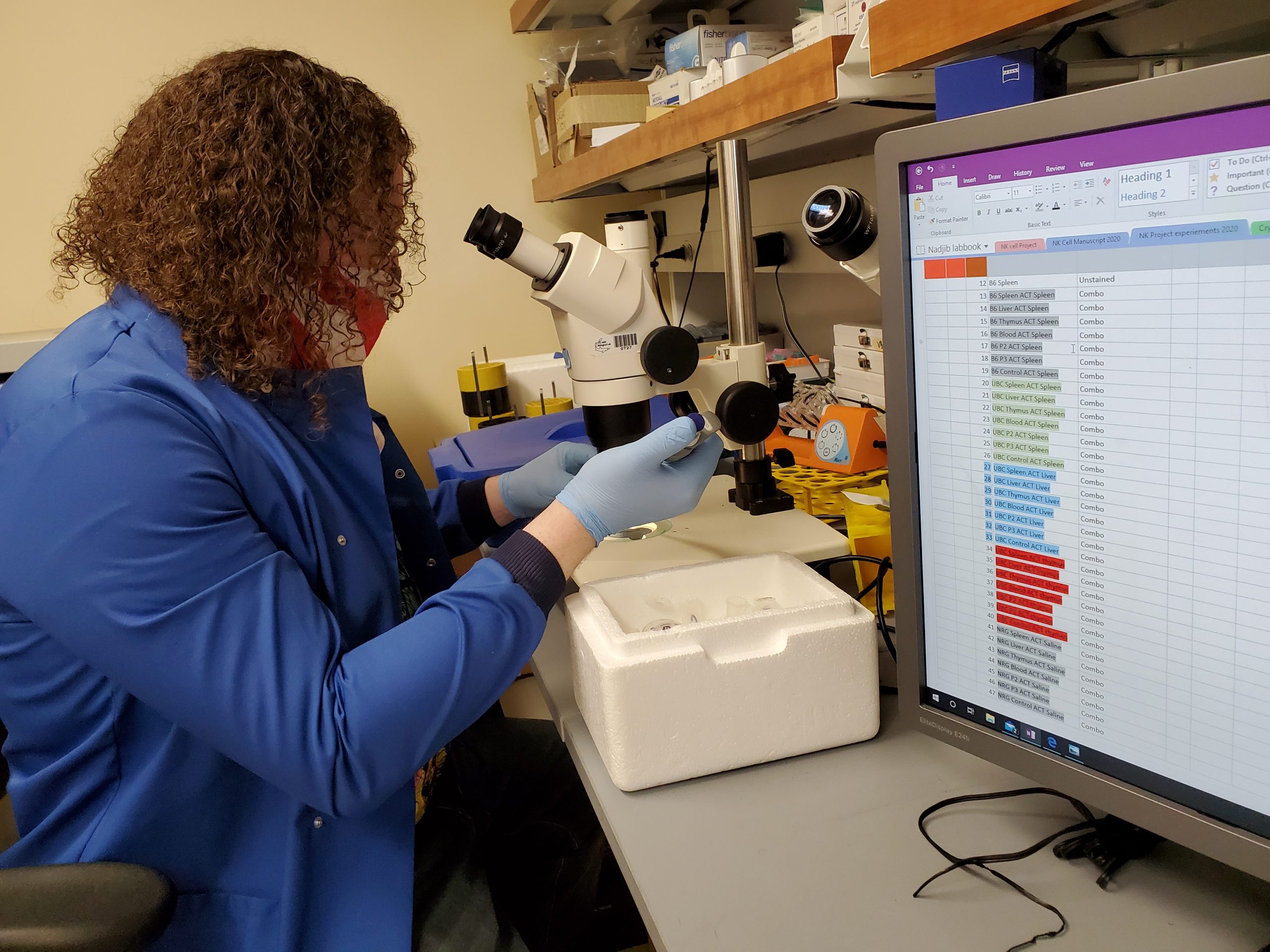

All of my research so far has been about cardiovascular genetics, but now I can do more experiments with proof of concept cellular agriculture. One of the biggest hurdles to growing tissue right now is getting it vascularized. I’m thinking that the best way to mimic a meat product might be to use a skeletal muscle cell and a cardiac endothelial cell. Even though skeletal muscle does have vasculature, it’s not as robust as the endothelial system in the heart. Since the heart needs so much oxygen, it has the most robust endothelial cells in the body. It sounds like a weird idea, but mixing and matching different cells from different organs might be the best way to grow meat in culture.

The pandemic hit just as you received the award. Has COVID-19 affected your work?

My lab isn’t shut down, but it’s severely limited so things are a lot slower. Working from home is great for writing though! I’ve been working on an essay about cellular agriculture and human rights for this AAAS essay contest, and as I’ve been writing it has been impossible not to talk about the pandemic.

Before the pandemic I used to think all we had to do was grow the best meat we can. Now I realize it’s actually about getting food to where people need it. We can’t just focus on the science side of it, because it’s just as much about politics. It’s anecdotal but my sister—she fortunately just got health insurance—but she didn’t have any for a while and with COVID, you can’t exactly be uninsured. But the government doesn’t care that her healthcare is tied to her employment, so she’s not really being represented in a way that is supporting her health.

So in terms of how COVID-19 has affected my work, I’m a lot more focused now on the role of the government in identifying where people need to be served, and using innovation in agriculture to meet those needs. Everyone should have a right to food, which is just as much about distribution as production.

Right—what’s the point of a vaccine if not everyone has access to it? We are so fixated on when a vaccine will be ready—much like our fixation with when cultured meat will come to market—that we neglect to think about how to ensure that everyone has access to the tech when it’s finally here.

A lot of companies tell this story about cultured meat which ends in platitudes about how they’re going to feed the world. Well I understand that you’re making a new kind of meat, but how is that feeding anyone who isn’t eating right now? Show me that you’re building a modular lab where you build it in a shipping crate and can drop the meat production pipeline anywhere. That would be developing the tech and getting it to the people that need it.

It’s always assumed that when people are hungry it’s because we’re not producing enough food. That’s not true. For this essay, I’ve been reading Amartya Sen about the Bengal Famine which happened almost 100 years ago. Churchill and the British Raj who ruled India at the time made a priority decision to divert food from the Indians to feed Europeans. The famine was man-made, and millions of poor Indians died because the people in power didn’t represent their interests.

It’s twisted that Churchill and his “fifty years hence” speech is quoted in almost every article about cultured meat—always in the context of how this tech can feed the world—when Churchill was responsible for making millions of Indians food insecure during the Bengal Famine.

It’s messed up! There’s this quote by Amanda Little that I really like instead: “Technology won’t save us, but judicious applications of technology can.”

What is a “judicious application” of cell ag?

I want to make sure that we’re growing meat to feed people and not just growing meat to give McDonald’s cheaper meat. Cell ag isn’t going to be a panacea for all hunger, but it can be one tool of many. What the government should be doing is identifying the needs of certain communities to figure out what technology can meet those needs. What resources do they have? What are they lacking? Then our representatives can work with creative scientists to figure out how to reinforce these systems with cell ag.

If there is a lot of land with no water—maybe we use a genetically engineered crop that needs no water. That would maximize food abundance in that environment. In a different environment like a city, there might be plenty of water and electricity. That’s where having lab space would be functional. So solving hunger won’t happen through one tech, but we can use cell ag to produce diversity in our food system.

How do you think we get the government on board? At least in the US, there has been no funding for cultured meat research.

I’m not sure, but we have to be vocal and talk to our representatives. If every American tweeted at the president that we want cultured meat, I think something would happen. The thing is, cellular agriculture is a complex science. We need scientifically literate representatives who can understand the things that they are legislating, and who have the people’s interests at heart. I think it’s all about getting representation in policy right. This is probably a Pandora’s box that I shouldn’t be opening myself, but to have representation in policy the first thing to do is really to overturn Citizens United. The government is supposed to think long term and dump money at things that might not be profitable right now, but will solve a need in the future.

I think the way forward is getting local governments on board with the idea of cellular agriculture early. Much like how some governments are building their own internet infrastructure. Maybe those same governments could start a small agriculture craft brewery that makes meat.

We’re beginning to see “Big Ag” companies like Tyson and Cargill dip their toes into cellular agriculture and invest in cultured meat companies. Do you think there’s a danger in the technology being co-opted?

There’s a fine line between industrial support to get this tech off the ground, and keeping it enough of a grassroots movement that people are invested and still reaping the benefits of all of this. With those big meat companies—if they were to make cultured meat, it would be entirely driven by their finances and not what we need in terms of nutrition.

I’d like for the tech to be open source with all these tiny labs making it. If any one lab has some emergency, we aren’t centralizing food production—that’s just asking for trouble.

How do you respond to people who say you are going to take jobs away from farmers?

I’m not trying to take the farmer’s job away. I’m trying to give the farmer a better job where they’re looking at fewer animals and giving them better care, which most farmers want to do.

I’m into the idea of scaling up cellular agriculture while scaling down industrial farming of animals. So we’re not shutting down the rearing of livestocks, we’re scaling them down. Instead of your farm having to produce X tonnage, you drop that tonnage down. The government already provides food surpluses. We can financially spot this transition as a collective. It’s just about having the forethought to do that.

I want to make sure farmers needs are represented as well. There are some people who will never be on board with the idea of clean meat. I think that’s ok. If I try to grow macrophages by themselves, I can’t. They need things from other cell types. When I mix in the other cell types, all of a sudden they start growing like crazy. That’s what happens in the tissue, and I really think that’s an analogy for our food system. Perhaps we need to essentially try to integrate all these different technologies and ways of producing food.

…🤯🤯🤯

To stay up to date on New Harvest research updates and events, sign up for our newsletter.