Let’s start with your elevator pitch! What is your research about?

I am working on growing beef in-vitro by developing scaffolds to co-culture muscle and fat animal cells. Fat and muscle cells prefer different growth environments, so I am working on creating a scaffold with regions of varying stiffness that cater to each cell type.

What drew you to this work?

I was a huge animal lover as a kid and very thrown off by anything like bones or blood that reminded me that meat came from a living animal. When I was seven, I started asking questions about meat and my mom was very honest about where it came from. I became a vegetarian and began researching factory farming online, which led me to the Humane Society. They mailed me pamphlets about factory farming, which I wound up taking to my fourth grade class and passing out to other kids. That gesture wasn’t well-received. I actually got made fun of for being a vegetarian. It was a learning moment for me that we can’t push our beliefs on others.

Do you see these alternative meat technologies as a way to reduce animal cruelty without pushing your beliefs on others, then?

Definitely. My mom grew up in Ecuador and there are a lot of foods in our culture that have dairy in them. Although I’ve significantly reduced my dairy intake, it’s been tough to give up on those meals altogether. That’s what drew me to cellular agriculture. There are cultural implications for eating the foods we do, and it’s hard to change eating behaviors. If we could provide cell-based alternatives that are sustainable and animal-friendly, that would be ideal.

How did you break into the world of cultured meat?

I’m actually a microbiologist by training. I knew I wanted to get a PhD after my Masters, but my previous research was about water quality in urban areas and I didn’t love working with bacteria in that context. I needed money, so I started work as a lab manager. One day, I was in the office having a brainstorming session about what I wanted to do in grad school. Like at all major points in my life, I went back to my fundamental interests. I’ve always taken issue with factory farming and the idea [of cultured meat] kind of popped into my head as a potential solution. What if we could grow meat in a lab? I honestly thought I came up with the idea!

That is a surprisingly common story! Multiple cultured meat scientists have told me that they believed to have “invented” the idea at first.

That’s so funny! I obviously immediately started googling and saw that it was already being done, but I found that comforting. It seemed like a crazy idea to take on by myself. The first name that came up was Mark Post, who I saw was scheduled to present at New Harvest’s 2017 conference. That’s how I found out about New Harvest and the Fellowship Program. I was so excited there was a nonprofit supporting this work. I immediately emailed Kate [New Harvest’s research director] who told me that I could get free admission to the conference if I did a poster presentation. The review of current studies that I submitted was actually rejected, but then I learned you could volunteer and still attend for free so I immediately signed up and booked a flight to New York.

Stephanie volunteered at New Harvest’s second annual conference at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn.

You began your New Harvest Fellowship in 2019. What happened between the 2017 conference and then?

After talking with Kate, I felt it would be most helpful to apply for the fellowship after already having a PI and tailoring my project to fill gaps in the research already being funded by New Harvest. I really wanted to wait to have a collaborative experience with my PI, so it was only after finding Dr. Rowat that I landed on my current project. It took many conversations for us to arrive at developing scaffolds as the best approach for contributing to the field. Then, I applied to New Harvest and got funded in Spring of 2019.

How did you find your PI?

It took me a while to find Dr. Rowat, my PI. I actually got shot down by a lot of other professors, so it is important to be persistent. Dr. Rowat was one of six co-leads for a program at UCLA addressing challenges of food, energy, and water sustainability which aligned perfectly with what I was interested in. I looked into each of their backgrounds and although Dr. Rowat primarily focused on mechanobiology using cancer cells, she also did food science on the side. That gave me the perfect blend of expertise for cultured meat. I cold emailed her and she responded really positively. You need to show you’re genuinely interested in a professor’s work and make those connections between their research and yours, to show that that your project will contribute to their lab.

You worked on plant-based meat as an intern at Beyond Meat, but you’ve chosen to focus on cell-based meat for your research. What moved you to concentrate on the latter?

One of the reasons I stuck with cultured meat is that there’s already a lot of developments with plant-based meat. It’s been on the market for decades. Now our efforts need to be focused on getting cultured meat to market. As a researcher, there’s also a lot more room for innovation with cell-based meats.

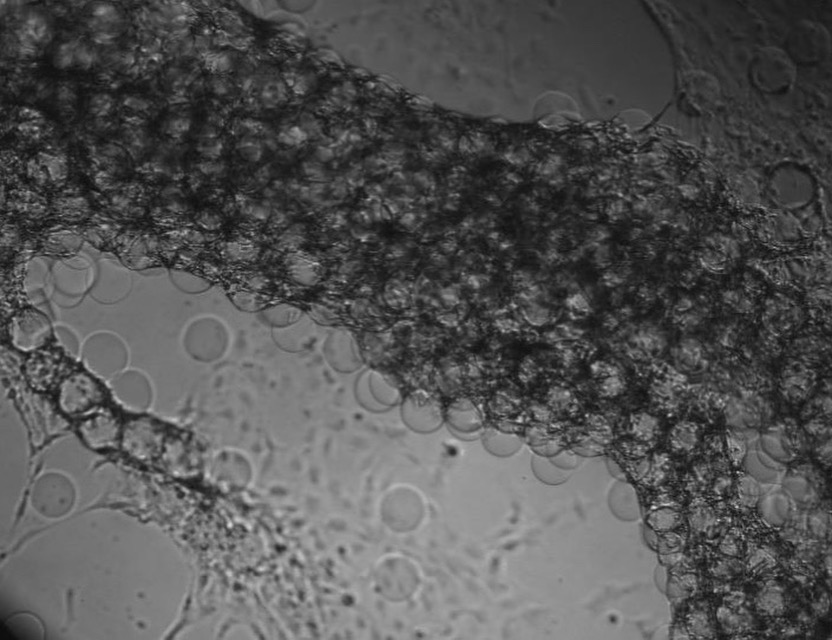

Fat cells on microparticle scaffolds. Fat gives meat texture and flavor, so it is crucial to develop a scaffold on which both muscle *and* fat cells can be cultured. Unfortunately, the two prefer different growth environments, so Stephanie is working on creating a scaffold with regions of various thickness that cater to each cell type.

What was it like working at a company, like Beyond Meat, versus working in an academic lab?

I honestly felt the vibe was way more similar than different. It seemed that everyone was on a similar page, and we’re really working toward the same goal: reducing the environmental impact of what we eat. We’re just going about it in different ways. I would say that projects change much more quickly in industry compared to academia. I found that challenging to navigate, since priorities would change and I felt like I wanted to see the project through.

Money-wise, it was very different! In academia you need to be smart about your money and go a lot further with less resources than at Beyond, which is a more established public company. I am honestly grateful for the penny-pinching experience, though. It makes me more resourceful, crafty, and I feel like a smarter scientist.

You mention that plant-based meats have been around for decades, that established history being one of the main reasons you’re focusing on cultured meat. Why do you think Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat are having such a moment right now, after decades of veggie burgers being relatively fringe?

I feel the next generation of plant-based meat have reached a technological breakthrough to be able to recapitulate the characteristics of conventionally-produced meat. The fact that they so closely resemble actual meat (color, taste, mouthfeel, cooking transitions) is an incredible stride for the industry. It caters more to omnivores, who value those characteristics of meat that previous plant-based meat products did not satisfy. I also think the timing of their popularity may be due to an increase in environmental awareness, specifically with younger generations such as millenials and Gen Z.

How would you compare plant- and cell-based meats, having worked with both?

The downside with plant-based meat is that it’s really hard to mimic the taste, texture, flavor and aroma of animal fat and animal protein with plant material. We’re getting better at it, especially with genetic engineering—but that might turn off a population that refuses to eat GMOs. To mimic meat as closely as possible, we also have to resort to using multiple ingredients and high processing, which can turn off some consumers as well. With cultured meat, I think it’s just still a very foreign idea to many people. We still can’t answer a lot of questions consumers have about what it’s going to taste like, how it’s going to be produced, and when it will hit markets. Some companies have projected within five years, but I think it’ll be a little bit longer. There are still a lot of hurdles we need to get over.

What do you think will be the first cultured meat products to come to market?

I definitely predict it will be a hybrid, or a blend, of plant-based meat and cultured meat cells. I’m curious to see how that will change the taste and texture of existing, fully plant-based meat. I can also see the first products being more specialized, maybe being served only by certain restaurants.

Ultimately, where do you hope to see all of this going?

The dream is that the three industries—cultured meat, plant-based meat and conventional meat—all work in harmony. I think each is going to cater to a certain consumer. There will still be consumers who eat only conventionally-produced meat, but the hope is that farmers move toward more sustainable practices to produce that meat, and that we produce less of it. Cell-cultured meat will cater to those who love the texture and taste of conventional meat, but who don’t love the animal suffering and environmental burden it entails. And from speaking with other vegetarians and vegans, I know there are also certain people who are just done with animal protein. They’re not going to convert to cultured meat, and they will continue to eat plant-based meat. I really see this all working together to reduce meat consumption. Just offsetting that consumption by a little bit could go a very long way for the environment.

To learn more about Stephanie, check out her project page.

This article was produced for New Harvest by Massive Science, a community of scientists telling fascinating, true stories about the science that’s happening now.